This selection of superb children’s titles, make up the breadth of my holiday kids recommendation list. They vary from hardcover picture books to intermediate, contemporary and classic. Mostly what they have in common is an indelible charm defined by quaint, universal narrative and extraordinary illustrations tailored to the specific texts. In this age of toddler marketing strategies, DVD parenting and extremely aggressive brand promotions, these books are standouts as prime examples of what should be at the center of story-telling for children- BOOKS.

The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane by Kate DiCamillo is shelved in the intermediate section of the children’s area, but is really very appropriate for children and adults of all ages. It tells the story of the porcelain rabbit, Edward Tulane. He begins a very vain little toy and ends up separated from his owner, proceeds on a very Homeric journey from a boxcar to the bottom of the ocean into a seaside village and eventually a home, generations later.

Toys Go Out: Being the Adventures of a Knowledgeable Stingray, a Toughy Little Buffalo, and Someone Called Plastic, is also intermediate reading, but all-ages appropriate. The chapters are interconnected but tell separate stories about the adventures these charming little toys have when humans leave the house. One story is called “The Terrifying Bigness of the Washing Machine”- it’s awesome. This was also published in 2006 and was written by Emily Jenkins.

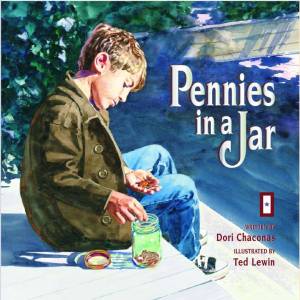

Pennies In a Jar by Dori Chaconas (Author) and Ted Lewin (Illustrator) tells the story of a young boy who promises to be brave when his father goes off to fight in World War II. The child lives in a world of air raid sirens and general wartime conditions. He, of course, meets a new friend who shows him that there are things to do for his father, even though he is so far away. Overall, this is great historical fiction for little people. Lewin provides great Rockwellian illustrations, very innocent. Chaconas is also a local Wisconsin author!

Crossing by Phillip Booth and When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer are also in this same classic narrative vein. An old-time steam engine rumbles past in Booth’s 1957 poem “Crossing” from his debut collection Letters from a Distant Land. The nostalgic illustrations by Bagram Ibatoulline (also, illustrator for Edward Tulane) invoke a longing for the simple act of waiting at the railroad crossing, the rattling boxcars.

Walt Whitman lends his poetry to When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer. Booklist offers a great synopsis: “Long's story-in-images makes a fine introduction for very young children. His interpretation of Whitman's eight-line rebuke of stuffy pragmatism tells a familiar story: A little boy obsessed with outer space has been dragged to an astronomy lecture. Unable to make sense of the speaker's pontifications, the fidgety youngster takes his toy rocket ship outside, where he marvels at the "perfect silence of the stars, casting a decisive vote for creative speculation over chilly analysis." I love this book so much, how rare to find a perfect adaptation of Whitman to add to a child’s important budding library.

The young boy in Wilfred Gordon Mcdonald Partridge spends his days in the retirement home next to his house. The relationships he forms with these wonderfully patient and wise elders are so darling. He is drawn on a skateboard mostly, weaving around the chairs. Wilfred’s favorite is Miss Nancy Alison Delacourt Cooper, who also has four names. Upon learning that she is losing her memory, Wilfred makes it his goal to give Miss Nancy enough of his own memories to take the place of what she has lost.

Finally, what I am most excited about this holiday season is the 10th-anniversary edition of Patricia Polacco's The Keeping Quilt, Polacco’s family story about a quilt made from an immigrant Jewish family's clothing from their Russian homeland. The story is very cyclical, chronicling the cross generational journey and multiple functions of this “keeping quilt.” The only color used is in the babushka and dress of Great-Gramma Anna, which become part of a brightly hued quilt. I love to quilt and recognize the importance of preserving one’s heritage through shared heirlooms. This book is beautiful.

Friday, November 30, 2007

New Downer Avenue Kids' Section!

Posted by

Anonymous

at

12:18 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: children's, historical fiction, holiday, intermediate, jewish, picture books, poetry, Sarah Marine, Wisconsin author

Tuesday, November 27, 2007

God Is Dead - Ron Currie, Jr.

No, it’s not Christopher Hitchens’ latest position paper; it’s an innovative collection of short stories woven around the powerful titular premise. The strangeness inherent in God Is Dead is owed to the fact that though God is dead (a victim of the genocide raging in

No, it’s not Christopher Hitchens’ latest position paper; it’s an innovative collection of short stories woven around the powerful titular premise. The strangeness inherent in God Is Dead is owed to the fact that though God is dead (a victim of the genocide raging in

Posted by

Justin Riley

at

11:14 AM

2

comments

![]()

Labels: apocalyptic, debut fiction, fiction, Justin Riley, religious, short fiction, speculative

Friday, November 23, 2007

15 Quick Recs from Eklund

John Eklund is a superhero/booklover who has many years experience in the book industry. He's formerly run a bookshop for Harry W. Schwartz and is currently a sales rep for Harvard UP, Yale UP, and MIT UP. To be fair, none of the following titles come from those publishers. Even if they did, if John was recommending them to me, I would pick them up.

In short: John actually reads all the books I want to read.

If any of these strike a chord, leave a comment, start a conversation.

Fifteen books I would love to give, receive, or read again in 2008

- by John Eklund

Le Ton beau de Marot: In Praise of the Music of Language

Douglas R Hofstadter

Basic Books 1997 $29.95

Hofstadter is a charming genius and every word he writes is worth reading. Here he shows how complex and fascinating the art of translation is by rendering Clement Marot’s short poem Ma Mignonne 88 different ways! One Day a Year

One Day a Year

Christa Wolf

Europa Editions 2006 $16.95

East Germany’s best writer kept a unique diary for 40 years- one short essay annually, written on the same day. She’s a great stylist, it’s a quirky take on the diary format- an intimate, insider’s view of a country going through monumental political change.

Robot Dreams

Sara Varon

First Second 2007 $16.95

The heartbreaking impossible friendship between a dog and a robot. I’m a tough customer when it comes to graphic novels but this is irresistible. The Air-Conditioned Nightmare

The Air-Conditioned Nightmare

Henry Miller

New Directions 1945 $13.95

It may be 63 years later but we’re still living it.

The Communist Manifesto

Karl Marx & Frederick Engels, intro by Eric Hobsbawm

Verso 1998 (orig. 1848) $16.00

In an era when the only books that seem to move millions of people are religious ones, it’s stunning to remember that this book once held sway over one third of the world. You can try reading it as a quaint, historical artifact if you want, but that won’t work for long- Marx’s descriptions of rapacious Capital are straight out of 2007 headlines. The Indian Clerk

The Indian Clerk

David Leavitt

Bloomsbury 2007 $24.95

My favorite novel of the year. Three towering intellects, an early 20th century British academic milieu, a scientific romance. I wouldn’t normally be drawn to a book about an Indian math wizard, and I’m usually put off by equations in novels, but this is so gripping, so beautifully told, that I immediately sought out the biography of the real life Ramanujan.

Independent People

Halldor Laxness

Vintage International 1997 (orig. 1946) $15.00

If the only thing that comes to mind when you think of Iceland is Bjork, mass inebriation, and bleak desolation, you need Laxness. This strange and wonderful epic is a good intro to his world. Don’t be put off by all the names like “Utirauthsmyri.” Just make up your own mental pronunciation and stick with it. The Society of the Spectacle

The Society of the Spectacle

Guy Debord

Zone Books 1967 $16.95

These 221 short theses by the French provocateur were written 40 years ago and describe a culture immobilized by the hypnotic power of the visual image. Sound familiar?

The Emigrants

W.G. Sebald

New Directions 1993 $10.95

The story of four German Jews in exile, told as a mock documentary complete with photographs. If you’ve not read Sebald- who tragically died in a car crash a few years ago- this is a good place to start. Tomorrow in the Battle Think on Me

Tomorrow in the Battle Think on Me

Javier Marias

New Directions 1994 $15.95

Ace bookseller Joe Lisberg got me going on this guy. I’ve blown through about a dozen of his excellent novels, and this one might be my favorite. He’s brilliant, and I don’t understand why he’s not better known and read in the US.

Collected Poems

Stevie Smith

New Directions 1976 $19.95

I first got acquainted with the sassy poetry of Stevie Smith after seeing Glenda Jackson portray her in the under-appreciated seventies biopic Stevie (it’s an outrage Netflix doesn’t have it). This is a witty, charming, deceptively light collection, complete with her eccentric drawings. The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories

Flannery O’Connor

Farrar Straus & Giroux 1972 $17.00

My friend Doug, who used to work at the Schwartz Grand Avenue store, couldn’t leave a customer alone until he talked them into reading O’Connor. He was right, there’s nobody like her. Choose any story and read the first paragraph. Then just try not to read the second.

Books on Trial: Red Scare in the Heartland

Shirley and Wayne A. Wiegand

University of Oklahoma Press 2007 $24.95

You would not believe what happened to an Oklahoma family in the forties when they had the nerve to open “The Progressive Bookstore” in that charming state. Some of the players in this gripping tale ended up in Milwaukee, and despite the ugly tactics of the thought police, there’s a somewhat hopeful climax: civil liberties actually won out over national security hysteria. The Story of Art

The Story of Art

E.H. Gombrich

Phaidon 2006 (orig 1950) $29.95

I have never taken an art history course so I’ve had a slight inferiority complex about the state of my art knowledge (or lack thereof). After reading Gombrich’s A Little History of the World last year, I thought I’d give this classic a try. It’s wonderful in every way- clear, no jargon, loaded with lovely images, and the sensuous design of this pocket edition really makes it fun to read and carry around.

The Book of Ebenezer LePage

G. B. Edwards

NYRB Books 2007 (orig. 1980) $16.95

If you read one book in 2008 make it this one. It’s a reminder of why books are worth reading. I have so much to say about it that I can’t really say anything. Just, read it.

Saturday, November 17, 2007

Pillars of Oprah's Earth

So, earlier this week Oprah's latest book club selection hit bookstores and the homes of ABC viewers via the large e-tailer-which-shall-not-be-named. Her selection? The multi-million copy selling The Pillars of the Earth by hugely popular writer Ken Follett.

In the New York Times Book Review for this same week, there was this boastful anecdote from Follett regarding a conversation he had with one of his friends, novelist and playwright Hanif Kureishi:

"We were talking about what the readers like," Follett says. "He said, 'I never think about the readers.' I told him, 'That's why you are a great writer, and that's why I am a rich writer.' "

Speaking of a rich Ken Follett, within a year of the original publication of Pillars, Follett signed with Dell Publishing for a $12.3 million two-book deal. All of his books have been bestsellers and several have been made into movies, and just announced in Publishers Weekly is a new $50 million deal for an epic trilogy by Mr. Follett.

Ken Follett is not undeserved of his reputation nor is it a bad thing for his book to be introduced to a cadre of new readers. My beef is not with Ken Follett or his skill in writing suspenseful tomes of historical fictition.

My beef here is with Oprah Winfrey and her book club. Clearly, based solely on the numbers of books he sells, the money he makes, or his own admission of writing for money, Ken Follett does not need any help in gaining readers. I also do not have a problem with writers hitting the gold coin jackpot, I just wish more of them could be making those big bucks.

Why not use the famed Oprah power of thrusting new books into readers hands that are by writers who have yet to find their fame anywhere beyond small literary circles of fandom? She has done so a handful of times and I do wish she would do it every time. Imagine what could be done for reading and emerging writers if Oprah championed these floating gems and diamonds in the rough.

Independent booksellers across the nation have catapulted books to bestseller-dom simply by the fine old art of handselling. Recent examples: Water for Elephants by Sara Gruen, Three Cups of Tea by Greg Mortenson and Eat, Pray, Love by Elizabeth Gilbert. Ms. Winfrey can even be thanked for featuring Ms. Gilbert on her show and assisting indie booksellers in thrusting this writer into newfound and well-deserved fame. Seeing what booksellers and Oprah can do for readers and writers, why not expand that power to the book club itself? We can even offer Ms. Winfrey a list of suggestions - should she need them.

reference sites:

Ken Follett is Latest Oprah Winfrey Pick, AP

Follett Cashes In On 'Century', PW

Homepage for Ken Follett

Posted by

StacieMichelle

at

6:38 PM

3

comments

![]()

Labels: book club, historical fiction, Ken Follett, Oprah, Stacie Williams

Tuesday, November 13, 2007

Feminist Bookstore

by Sarah Marine

I regularly check the New York Times online book blog Papercuts; it's worth the trip. I am of course, if you know me, attracted to the most scathing wit and straight-faced criticism out there and the short film Feminist Bookstore recently posted on Papercuts happens to be just that. Carrie Brownstein of the legendary punk-rock OLY WA band Sleater-Kinney and Saturday Night Live's Fred Armisen are the new comedic duo called Thunderant, which created the short. The film features Brownstein and Armisen as two feminist bookstore employees deciding for or against hanging different flyers in their store window. As a feminist, a bookstore employee and some-percent hippie it's pretty right on with its humor and criticism. Check it out.

Makes me wish Chic Ironic Bitterness was getting better reviews than this.

Monday, November 12, 2007

Pat Conroy & the Chemistry of Combustible Books

by Jay Johnson

Sure, this missed Banned Books Week by a month, but shouldn't we be thinking of the dangers of censorship year-round anyway? I think so.

In a Gazette article about the school board's cultural prescription, I found the following interesting:

October 24, 2007

Pat Conroy’s letter about Nitro High's book suspensions

· Author scolds censors, praises teachers and students

A Letter to the Editor of the Charleston Gazette:

I received an urgent e-mail from a high school student named Makenzie Hatfield of Charleston, West Virginia. She informed me of a group of parents who were attempting to suppress the teaching of two of my novels, “The Prince of Tides” and “Beach Music.” I heard rumors of this controversy as I was completing my latest filthy, vomit-inducing work. These controversies are so commonplace in my life that I no longer get involved. But my knowledge of mountain lore is strong enough to know the dangers of refusing to help a Hatfield of West Virginia. I also do not mess with McCoys.

I’ve enjoyed a lifetime love affair with English teachers, just like the ones who are being abused in Charleston, West Virginia, today. My English teachers pushed me to be smart and inquisitive, and they taught me the great books of the world with passion and cunning and love. Like your English teachers, they didn’t have any money, either, but they lived in the bright fires of their imaginations, and they taught because they were born to teach the prettiest language in the world. I have yet to meet an English teacher who assigned a book to damage a kid. They take an unutterable joy in opening up the known world to their students, but they are dishonored and unpraised because of the scandalous paychecks they receive. In my travels around this country, I have discovered that America hates its teachers, and I could not tell you why. Charleston, West Virginia, is showing clear signs of really hurting theirs, and I would be cautious about the word getting out.

In 1961, I entered the classroom of the great Eugene Norris, who set about in a thousand ways to change my life. It was the year I read “Catcher in the Rye,” under Gene’s careful tutelage, and I adore that book to this very day. Later, a parent complained to the school board, and Gene Norris was called before the board to defend his teaching of this book. He asked me to write an essay describing the book’s galvanic effect on me, which I did. But Gene’s defense of “Catcher in the Rye” was so brilliant and convincing in its sheer power that it carried the day. I stayed close to Gene Norris till the day he died. I delivered a eulogy at his memorial service and was one of the executors of his will. Few in the world have ever loved English teachers as I have, and I loathe it when they are bullied by know-nothing parents or cowardly school boards.

About the novels your county just censored: “The Prince of Tides” and “Beach Music” are two of my darlings, which I would place before the altar of God and say, “Lord, this is how I found the world you made.” They contain scenes of violence, but I was the son of a Marine Corps fighter pilot who killed hundreds of men in Korea, beat my mother and his seven kids whenever he felt like it, and fought in three wars. My youngest brother, Tom, committed suicide by jumping off a fourteen-story building; my French teacher ended her life with a pistol; my aunt was brutally raped in Atlanta; eight of my classmates at The Citadel were killed in Vietnam; and my best friend was killed in a car wreck in Mississippi last summer. Violence has always been a part of my world. I write about it in my books and make no apology to anyone. In “Beach Music,” I wrote about the Holocaust and lack the literary powers to make that historical event anything other than grotesque.People cuss in my books. People cuss in my real life. I cuss, especially at Citadel basketball games. I’m perfectly sure that Steve Shamblin and other teachers prepared their students well for any encounters with violence or profanity in my books just as Gene Norris prepared me for the profane language in “Catcher in the Rye” forty-eight years ago.

The world of literature has everything in it, and it refuses to leave anything out. I have read like a man on fire my whole life because the genius of English teachers touched me with the dazzling beauty of language. Because of them I rode with Don Quixote and danced with Anna Karenina at a ball in St. Petersburg and lassoed a steer in “Lonesome Dove” and had nightmares about slavery in “Beloved” and walked the streets of Dublin in “Ulysses” and made up a hundred stories in the Arabian nights and saw my mother killed by a baseball in “A Prayer for Owen Meany.” I’ve been in ten thousand cities and have introduced myself to a hundred thousand strangers in my exuberant reading career, all because I listened to my fabulous English teachers and soaked up every single thing those magnificent men and women had to give. I cherish and praise them and thank them for finding me when I was a boy and presenting me with the precious gift of the English language.

The school board of Charleston, West Virginia, has sullied that gift and shamed themselves and their community. You’ve now entered the ranks of censors, book-banners, and teacher-haters, and the word will spread. Good teachers will avoid you as though you had cholera. But here is my favorite thing: Because you banned my books, every kid in that county will read them, every single one of them. Because book banners are invariably idiots, they don’t know how the world works — but writers and English teachers do.

I salute the English teachers of Charleston, West Virginia, and send my affection to their students. West Virginians, you’ve just done what history warned you against — you’ve riled a Hatfield.

Sincerely,

Pat Conroy

Is it surprising that a physical scientist's answer to this problem is an unwavering faith in the triumphant privileging of rationalism? Oh, the Enlightenment and its progress in rationalism! More labels, more categories, Mr. Raglin. Perhaps a factory of book rating (good books go to the sleeping chambers, bad ones go where?) would appeal to him, as the prevalent model of the century of camps (thank you, Zygmunt Bauman - excerpt) would be recognizable to rational logic.Board member Bill Raglin was not sympathetic.

“That fool, Conroy, assumes ... that every person who is an English major [or teacher] is above reproach,” Raglin said. “I’m a chemist. Do I believe that all chemists are good? No.

“Maybe I should go back to school and change my major.”

He favors a book rating system or disclaimers on controversial books.

And, yes, you should go back to school; as a person who occupies a position of leadership in the community - I won't cite you as a role model - you should be continually expanding your knowledge, growing your field of perception. Chemistry has changed since you graduated; so has the world, whether you're with it or against it. As a school board member, I would expect Mr. Raglin to be supportive of continuing education. But, I suppose I'm confusing advocacy with board membership.

If he does return to school, perhaps he will see the disconnect in his confusing reproach with a qualitative pronouncement of value. It's censure, Mr. Raglin, not censor. At least we can agree that there are bad chemists - and be glad they aren't concerned with the teaching young Americans to think critically and independently. Clearly, English teachers - not Chemists - should be in charge of that.

Sunday, November 4, 2007

Bonesteel. Then Ander Monson.

In preparation for my annual rendezvous with Ander Monson’s devastating work on the upper Midwest, the stark narratives investigating the smell of static that penetrates all winter outerwear, the line of communication labeled, Other Electriticites,

In preparation for my annual rendezvous with Ander Monson’s devastating work on the upper Midwest, the stark narratives investigating the smell of static that penetrates all winter outerwear, the line of communication labeled, Other Electriticites,

I have been gathering into myself the works of Richard Hugo and Mike Balisle. You may reply, “Oh, Richard Hugo, yeah, we know Richard Hugo- but, who’s that Mike Balisle?”

Balisle. You may reply, “Oh, Richard Hugo, yeah, we know Richard Hugo- but, who’s that Mike Balisle?”

Well, curious reader, let me tell you, Mike Balisle penned a collection in 1977, entitled Bonesteel. It is self-published, held together by staples and yellowed by years. I found it in a box at the Renaissance Bookshop in downtown Milwaukee. The fiction at Renaissance is, for the most part, well picked over by Marquette bibliophiles, but the other sections, especially the children’s, are overflowing with yet to be discovered phenomena. So, anyway, I have been carrying this slight volume- Bonesteel- around for about two weeks, taking out and reciting any of the hundreds of amazing prose to whomever happens to be standing the closest- most often boyfriend type person. I have looked online and found nothing on the author or the collection.

"With Unknown Fever"

at that time the holy men of the upper Midwest would strip naked under the

northern lights and fight like angry blacksmiths until caving in gloriously

I imagine Mike Balisle as some silent small-town Midwestern boy, eating lunch at eleven and dinner at five like clockwork, plowing driveways or working construction, this book a brief foray into creativity. He was probably just some fashion vagabond, tramping around the country on trains or flatbed trucks, only to return to place of birth and ultimately become the aforementioned small-town personality. Or maybe he’s in some D.C. think tank or perhaps he lives down the street from me, muttering daily about the price of gasoline.

"The White Axes of Winter"

years inside a blizzard we awaken

to the questioning of the fact

that last night pale children were stalked

by images of ice

this morning it is seen

the white axes of winter whirled until all

oaths and prayers were split from our faces

there we fell

the cold hills

drifting our shoulders

Dear Mike Balisle,

You’re making it difficult for me to move beyond:

I will forget my sadness

and run with lengthening legs

to the tavern in junction city

where anna in her wheelchair

presents me with a grain belt

and

“the soul lives on----don’t you know that yet?”

I mean, this kind of language compounded with the new Weakerthans album (Night Windows may be the most satisfying devastation track of the year), is prohibiting me from doing anything but obsessively consuming them exclusively.

In conclusion, Mike Balisle, I appreciate your work, and hope that somewhere along the line, someone, someone not on an obscure book blog in 2007, someone you knew in the thirty years between Bonesteel and now, was smart enough to tell you that in person.

Posted by

Anonymous

at

1:02 PM

2

comments

![]()

Labels: fiction, midwest, poetry, Sarah Marine, self-published, winter

Daniel Goldin Asks Ellen Litman To Explain, Explain

This interview was conducted by Daniel Goldin, the senior front list buyer for Harry W. Schwartz Bookshops. Some questions for Ellen Litman, author of The Last Chicken in America; but first, some jabbering...

Some questions for Ellen Litman, author of The Last Chicken in America; but first, some jabbering...

Welcome to my first posting on the Schwartz blog, The Inside Flap. I have worked for this group of independent bookstores in the Milwaukee area since 1986, and currently do a bunch of new book buying as well as some manager-y stuff.

I have been told that the key to blog success (blogwise) is linking to other blogs. To that end, I would like to do a shout out to Arsen Kashkashian at Kash’s Corner and Megan Sullivan The Bookdwarf in the desperate hope that they will then link here.

And a special yodel to my sister company, 8CR, who is bloggarific!

I referenced Megan in a Schwartz email newsletter (which you can read here) in which I extolled the virtues of Ben Percy’s short story collection Refresh Refesh. I’m glad to say it’s getting extremely good reviews everywhere, though not everybody likes the speculative stories. I thought it was great the way Percy did a lot of genre bending, yet always stayed connected via setting and themes.

We’re hosting Ben Percy at our Downer Avenue shop on Monday November 5th, along with another budding short story writer, Ellen Litman, author of The Last Chicken in America. The stories take place among the Russian Jewish immigrant community of Pittsburgh’s Squirrel Hill, centered on one Ellen-like character named Masha. They are funny, provocative, innocent yet worldly, and filled with arresting details, such as the tidbit that her father has a different job in almost every story. And funny, did I mention that? I like funny.

Here, in modern epistolary form, is our Q&A, with one caveat. I lost my original questions and had to reconstruct them. Goldin: I love your book so much. I hope you don’t mind that I am writing to you out of the blue with these questions. I got permission from your publicist!

Goldin: I love your book so much. I hope you don’t mind that I am writing to you out of the blue with these questions. I got permission from your publicist!

Litman: Thank you for your message. I'm very excited about coming to Milwaukee to read at Schwartz! I spent a year in Madison and managed to take a couple of trips to Milwaukee while there, usually to go to readings. And I'm looking forward to meeting Ben Percy. I've been hearing a lot about him lately.

Thank you, also, for your kind words about the book!

Goldin: I’m assuming the book’s somewhat autobiographical. What’s true; what’s not?

Litman: I did live in Squirrel Hill, for 3 years. My family came to Pittsburgh from Moscow, in 1992, and my parents still live there. So, much of the book did come from my experiences of the early years there. I was 19 at the time we immigrated, a bit older than Masha, the main character in the book. But like her, I studied computers at the University of Pittsburgh.

Goldin: What led you to start writing?

Litman: For a while I was a computer programmer, not daring to even imagine I could write in English. (Though writing was what I always wanted to do.) Then, eventually, I signed up for a fiction writing class, and when that went well, I signed up for another one. And so on. I was living in Boston at the time, working for a software start-up. I would get up really early in the morning and write for a couple of hours before going to work. I thought, at first, that's what I would do: work as a programmer, write on the side. Except I was tired a lot and I was starting to realize that I needed to put more time into writing and that writing was becoming a lot more important to me than computer programming. So I followed my teachers' advice and applied to MFA programs.

Goldin: What was the inspiration for this collection of stories? Which story came first?

Litman: The first story I wrote about Russian immigrants in Squirrel Hill actually didn't make it into the book. It was called "Engagement" and I wrote it in the first person plural (inspired by The Virgin Suicides, which I love!). It was my first published story. But in the end I had to leave it out. It was covering the same territory as some other stories in the book, and these other stories were doing it better. Goldin: What was left out? What was changed? (editor’s note: I find that one gets very interesting answers to this question at readings. I learned that Audrey Niffenegger’s heroine in The Time Traveler’s Wife originally ended up institutionalized—who knew? Try asking it the next time you attend an author reading.)

Goldin: What was left out? What was changed? (editor’s note: I find that one gets very interesting answers to this question at readings. I learned that Audrey Niffenegger’s heroine in The Time Traveler’s Wife originally ended up institutionalized—who knew? Try asking it the next time you attend an author reading.)

Litman: There were some other stories that got left out. By the time I finished my MFA (at Syracuse), I had a version of this book ready. Then I had a couple of agents read it, and they pointed out that a lot of the stories felt too similar. So I had to rethink the whole thing. The following year (while I was in Madison on fellowship), I rewrote it. I ended up leaving out 3 stories and writing 4 new ones. Most of the new ones were about Masha, the main recurring character.

Goldin: What are you working on now? More stories or a novel or another hybrid?

Litman: I *am* working on a novel now. A "real" novel, which is to say, not in stories. And it's a whole new game, of course, and I feel like I'm floundering all the time, which I guess is normal. It's set in Moscow during the Perestroika years, so in the name of research I get to re-watch a lot of old Soviet movies.

Goldin: What was the glaring difference to you about life in the US versus pre-immigration, and in this, I'm looking for an unexpected answer, not, for example, that you used to speak in Russian.

Litman: Probably how different people looked. There were various ethnicities in Russia, too, but hardly any people of color. Also, you saw few people with serious disabilities. There seemed to be so many of them in America, it was kind of alarming. Of course, in reality, there had been just as many in Russia, but they were hidden. There was simply no place for them there, no way to go outside, no buses that could accommodate wheelchairs, etc.

Goldin: Who do you like to read a) living b) dead c) famous d) not so famous?

Litman: That's a tough one, because I always feel l'm missing so many. But I'll try:

a) George Saunders, Jeffrey Eugenides, Mary Gaitskill

b) Chekhov, Bulgakov, Edith Wharton, John Galsworthy

c) Philip Roth

d) Kelly Link, Gary Lutz

(editor’s note: While we and many independent bookstores carry works from the first nine authors, Mr. Lutz’s collection Stories in the Worst Way, seems to have come out from Knopf in 1996 and is now out of print—alas! For those like me that always need to know more, Mr. Galsworthy’s most famous book is The Forsyte Saga, and he won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1932.)

Goldin: What’s the best Russian book that hasn't been translated into English?

Litman: There's a book I read as a teenager and always loved. It's not even *that* well known in Russia, but among those who've read it, it has sort of a cult following. It's called The Road Disappears into the Distance, by Aleksandra Brushtein, and it's about a young girl growing up in pre-Revolutionary Russia, in a small town that's half-Russian/half-Polish, and gradually becoming aware of some heartbreaking realities around her (poverty, inequality, chauvinism) and what it takes to be a decent human being.

Goldin: Who do you think made the best French Fries in Pittsburgh?

a. Primanti Brothers (multiple locations, but only the Strip District is 24 hours)

b. Original Hot Dog (O's) in Oakwood

c. The Potato Patch at Kennywood Park

d. Someplace else

e. French fries are bad for you

It's kind of shameful to admit, but of the places you've listed, I've only been to Original. Once! What can I say, my parents don't eat out much even now, and as for me, it took me a while to get used to the idea. I think I used to buy cheeseburgers from McDonald's on campus. And coffee. No fries.

Ellen Litman teaches creative writing at the University of Connecticut, Storrs.

She will be appearing at the Schwartz Bookshop on Downer Avenue, 2559 North Downer Avenue, on Monday, November 5th (2007) at 7 PM. Their phone number is 414-332-1181.

Posted by

Anonymous

at

12:21 PM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: Daniel Goldin, debut fiction, event, immigration, interview, Russian, short fiction, women writers